The Environmental Protection Agency on Wednesday said it plans to do outreach to communities where there are elevated cancer risks — including Lakewood — because of medical sterilization facilities that use ethylene oxide in their operations.

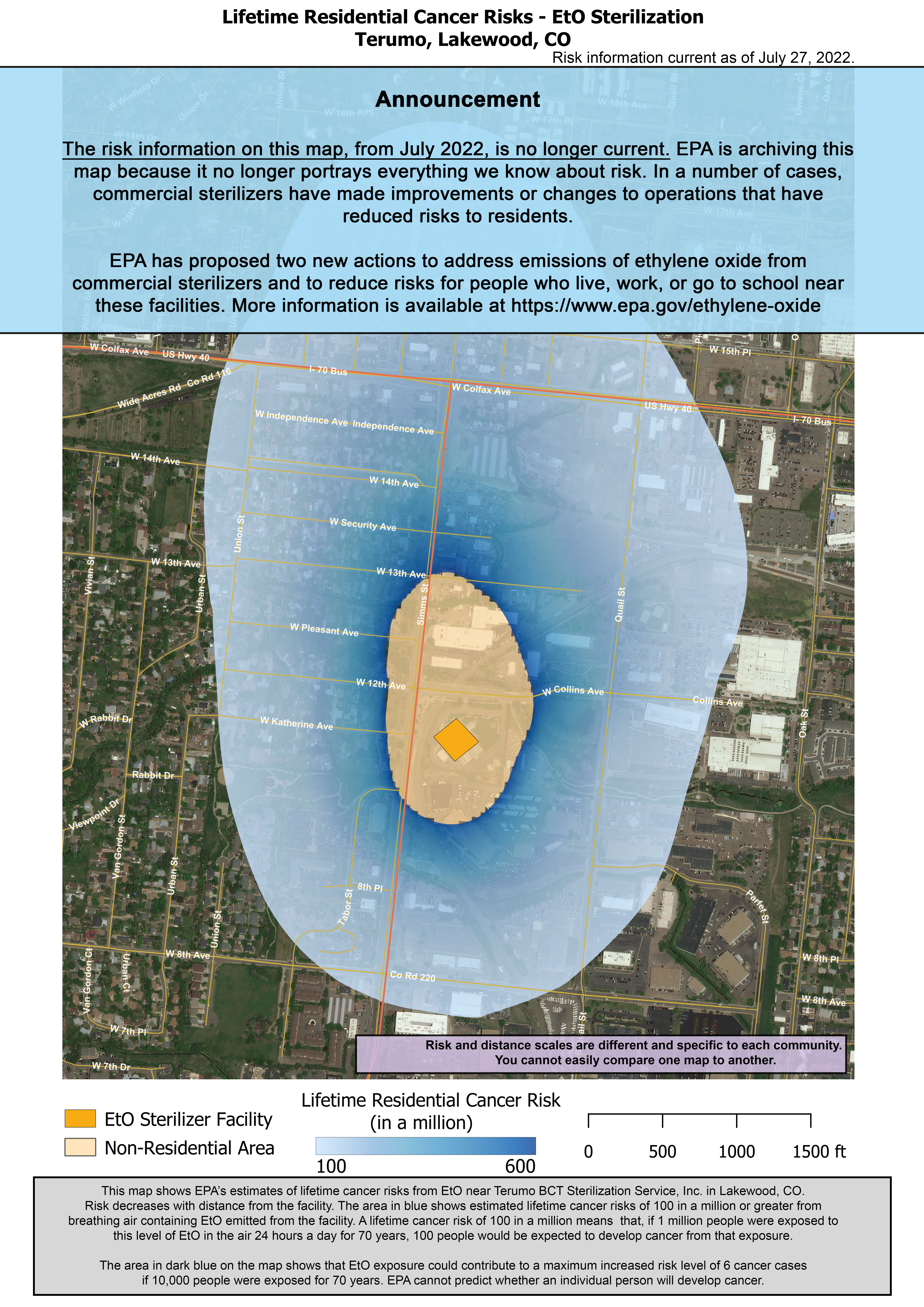

Terumo Blood and Cell Technologies, which has a facility at 11308 W. Collins Ave., was one of 23 commercial sterilization plants in the United States and Puerto Rico that were placed on the EPA’s high-risk list after an assessment that involved emissions testing and modeling, the EPA announced Wednesday.

A recently completed risk assessment of the impact of Terumo’s ethylene oxide emissions “identified elevated cancer risk in the Lakewood community,” the EPA wrote on its page about the Colorado location.

Terumo runs a manufacturing facility in Lakewood that makes health care products and it operates a nearby plant where that medical equipment is sterilized before it is delivered to doctors’ offices, laboratories and hospitals, said Jessi Done, Terumo’s vice president/senior plant manager for sterilization.

The company also has a manufacturing plant in Littleton, but that site does not have a sterilization facility, Done said.

Ethylene oxide is used to clean everything from catheters to syringes, pacemakers and plastic surgical gowns.

While short-term or infrequent exposure to ethylene oxide does not appear to pose a health risk, the EPA said long-term or lifetime exposure to the chemical could lead to a variety of health problems, including lymphoma and breast cancer. The EPA said it is working with commercial sterilizers to take appropriate steps to reduce emissions.

“Today, EPA is taking action to ensure communities are informed and engaged in our efforts to address ethylene oxide, a potent air toxic posing serious health risks with long-term exposure,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said in a statement Wednesday.

The EPA will conduct public outreach campaigns in each of the communities where elevated risks have been found, including a national public webinar on Aug. 10 and a community meeting for Lakewood residents on Oct. 25.

Terumo’s Lakewood plant holds its emissions below permitted levels, Done said. The company already converts used ethylene oxide to ethylene glycol, which is recycled for use as a primary ingredient in antifreeze for cars.

And in 2023, the company will install a new $22 million emissions system that will capture more ethylene oxide and reduce it to water vapor and carbon dioxide, sending less into the air, she said.

In 2018, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment studied the state’s cancer registry and determined that cancer incidences among residents living near the Lakewood facility were no more elevated than in other parts of the state. Then-director Dr. Larry Wolk said the state would do more testing.

The state health department’s most recent data on Terumo’s emissions is from August to October 2018, when the agency found additional controls installed at the facility resulted in a two- to five-fold reduction in cancer risk to nearby residents, spokeswoman Leah Schleifer said in an emailed statement Wednesday.

The new emissions controls resulted in a reduction in ethylene oxide concentrations around the facility.

“EPA’s new maps and data are consistent with CDPHE’s prior air sampling data and risk assessments,” Schleifer wrote. “EPA’s new modeling results help us even better understand the source of ethylene oxide emissions from the facility. That gives us new and critical information to consider for regulation and permitting.”

But Done said the EPA’s estimates are based on computer modeling, whereas the state has conducted actual emissions testing.

“The information the EPA will share is based on computer modeling, but there’s actual testing that was done to show there is no increased incidents of cancer in the community surrounding Terumo BCT,” Done said.

Lakewood, Laredo, Texas, and Ardmore, Oklahoma are among the communities facing the highest risk from ethylene oxide emissions, the EPA said.

Laredo is a border city where the vast majority of residents are Latino and more than a quarter live in poverty. Missouri-based Midwest Sterilization Corp. operates a sterilization plant in Laredo. The company also owns a plant in Jackson, Missouri, that is on the EPA’s watch list.

More than 40% of Laredo’s nearly 70,000 schoolchildren attend campuses in areas with an elevated risk of cancer due to ethylene oxide emissions from the Midwest plant, according to an analysis by ProPublica and the Texas Tribune.

A spokesperson for Midwest declined immediate comment. But the company told ProPublica and the Tribune last December that the cancer risk from its Laredo plant is overstated. Emissions it reported to the EPA are “worst case scenarios,” rather than specific pollution levels, the company said.

The Ethylene Oxide Sterilization Association, an industry group, said in a statement that ethylene oxide has been used for decades by the health care community to sterilize a wide variety of medical devices and equipment. More than 20 billion health care products are sterilized each year in the U.S. alone.

In many cases, there are no practical alternatives currently available to ethylene oxide, the group said, adding that use of less effective cleaning methods “could introduce the real risks of increased morbidity and mortality″ at hospitals throughout the country.”

The EPA called medical sterilization “a critical function that ensures a safe supply of medical devices for patients and hospitals.″ The agency said it is committed to addressing pollution concerns associated with EO, sometimes called EtO, “in a comprehensive way that ensures facilities can operate safely in communities while also providing sterilized medical supplies.”

Proposed rules to update control of air toxic emissions from commercial sterilizers and facilities that manufacture EtO are expected by the end of the year, with final rules likely next year, EPA said.

Scott Whitaker, president and CEO of the Advanced Medical Technology Association, another industry group, applauded EPA “for its forthrightness about what it does and doesn’t know” about EtO, but added: “It is critical that the EPA get this right.″

A potential shutdown of medical-device sterilization facilities “due to misinformed political pressure, as well as uncertainty regarding which regulations the facilities must adhere to …. would be disastrous to public health,″ Whitaker said in an email.

At least seven sterilizers on EPA’s watch list are AdvaMed members, including both Midwest plants and two owned by industry giant Becton, Dickinson and Co., also known as BD.

Besides medical cleansers, EtO is used in a range of products, including antifreeze, textiles, plastics, detergents and adhesives. It is also used to decontaminate some food products and spices. Two of the 23 facilities targeted by EPA — in Hanover and Jessup, Maryland — are used to sterilize spices. Both are operated by Jessup-based Elite Spice.

Other commercial sterilizers cited by EPA are located in Groveland, Fla.; Salisbury, Md.; Taunton, Mass.; Columbus, Nebraska; Linden and Franklin, New Jersey; Erie and Zelienople, Pa.; Memphis and New Tazewell, Tenn.; Athens, Texas; Sandy, Utah; and Richmond, Virginia.

Four plants are in Puerto Rico: Anasco, Fajardo, Salinas and Villalba.

The EPA’s announcement shines a light on health threats that sterilizer facilities pose to millions of Americans, said Raul Garcia of the environmental group Earthjustice.

“Now that EPA has new information on precisely where the worst health threats are, the agency must use its full authority to … require fenceline monitoring at these facilities (and) issue a strong new rule,″ he said. “No one should get cancer from facilities that are used to sterilize equipment in the treatment of cancer.”